Carol Menaker's New Book Looks at Jury's Error

Back in the summer of 1976, when Carol Menaker reported to a Pennsylvania courthouse for her first jury-duty assignment, she never anticipated that the next three weeks would leave a decades-long impression on her.

Frederick Burton, an inmate on trial for the murder of the warden and deputy warden of Philadelphia’s Holmesburg prison, faced life imprisonment if found guilty. And Carol -- (who believes she was “too young, too naive, too white, and too privileged”) -- along with 11 other jury members, had a tough decision to make.

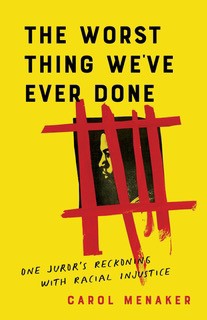

Carol’s new book, The Worst Thing We’ve Ever Done, details her 21-day sequestration experience, culminating in a verdict which, she believes, went the wrong way.

-“If he was in the room, he’s guilty.”

While it was undisputed that Burton had been present when the murders occurred, the facts revealed that another inmate (who was also present at the time) was wholly responsible. Carol recalls vacillating arguments between Burton’s (“Johnny Cochrane-esque”) defense attorney and the Pennsylvania DA, (“who was more akin to Perry Mason”), and how much of the trial involved discerning which version of the facts the jury wished to believe.

“The only way to make that decision was to have a bias,” Carol said, in an exclusive interview with us, and this jury had to choose between the word of the captain of the prison guards, or that of an already-convicted black man.

Thinking back, Carol recalls that the crux of her decision hinged on the judge’s jury instruction immediately prior to deliberation. Carol remembers the judge noting, in so many words, “If he was in the room, he’s guilty.”

That instruction relates to the “felony-murder rule,” which generally allows a court to hold a defendant responsible for a murder that occurs during the commission of a crime, even if the defendant didn’t commit the killing.

Carol remembers thinking at the time that the instruction was unfair, but because she believed it was her duty to follow the judge’s guidance, she voted guilty. “It didn’t matter what either attorney said at that point,” Carol added.

In the end, Burton was convicted of 2nd degree felony murder in the death of one of the wardens, and sentenced to life without parole.

-“I went back to work, but 50 years later he’s still in jail.”

After the trial, Carol’s normal routine resumed. And it wasn’t until some 40 years later, when another jury service letter from the state -- (around the same time as the Black Lives Matter protests, and George Floyd’s murder) -- that Carol reflected on her earlier experience, and how she now believes a grave mistake was made.

Carol began to research information on Burton and discovered that he had been sentenced to prison for his purported role in the murder of a white police officer in Philadelphia in 1970 – in a case known as the “Philly 5.” Carol wasn’t informed of that prior conviction during the course of her jury service, but later came to learn that perhaps Burton was innocent of that “Philly 5” crime as well.

“He was in the wrong place at the wrong time … twice.”

Prior to “Philly 5,” Burton was a well-respected member of his community, working for a phone company, married, a father of two, and expecting twin babies.

Hugh Williams, a “black Revolutionary,” and an acquaintance of Burton’s, had been the primary actor in the murder of the officer, and faced the death penalty. Williams’s wife was forced to testify to the crime, and during questioning, implicated Burton by association. Her statements, however, did not unequivocally place Burton at the scene when the murder occurred. She simply testified that Burton was in the same house as Williams when a Revolutionary meeting may have been taking place.

While the evidence was thin at best, the “Philly 5” case was racially charged, and the historical backdrop was that of widespread, systematic racism within Philadelphia’s police force; then under the direction of infamous Police Commissioner, Frank Rizzo.

As Carol dug deeper (undertaking meticulous research and interviewing Burton’s attorneys), she uncovered court filings which suggested that the Philadelphia DA’s office had suppressed exculpatory evidence which would have exonerated Mr. Burton all those decades ago.

It turns out that Williams’s wife had recanted her statements about Burton at a Philadelphia police station, stating that she had testified under duress and that the prosecutor and police had forced her to lie and implicate Burton. But her exonerating statements were never handed over to Burton’s lawyers. And from what Carol knows about the 1976 trial, she now believes that Burton was in the wrong place at the wrong time, twice, and that he has spent nearly his entire life in prison even though he’s never killed anyone.

-“Nobody won, except the law … and I think the law was wrong.”

And while Carol now states that she shouldn’t have convicted Burton based on the felony-murder rule, she believes the fault lies with her not having been properly educated by the court and that she was unaware of the gravity of her decision and the implications it would have on another human being.

It’s no secret that jury service has become a process that most Americans despise. The concept of it being your “civic duty” has completely deteriorated, and it’s now viewed as an onerous, time-consuming annoyance, rife with financial, emotional, and psychological burdens. Many Americans no longer respect, or care about, the process, and if you find yourself serving on a jury these days, you’ll mostly be kicking yourself because you couldn't weasel your way out.

While her memory is vague on the instructions given to her regarding her responsibilities as a juror, Carol now feels they weren’t nearly enough to properly equip her and her fellow jurors for the decision that rested in their hands.

Carol also remembers the jury-selection, or “voir dire,” process as being quite alienating, noting that it made her feel like a “pawn.” She believes that the attorneys focused too heavily on people’s biases and that they had thus corrupted the pool. She remembers only two substantive questions asked of her:

“Do you think everything a police officer says is true?”

“Do you think he’s guilty just because he’s black?”

Carol is of the view that if she had been made aware of the finer points of the felony murder rule during voir dire, she would have relayed her discomfort making that kind of decision, “I don’t know where the [jury] education happens, but it didn’t happen for me, and it doesn’t happen for a lot of people.”

-“When there’s someone else’s life at stake, there’s no reason to hurry.”

So how might the American legal system accomplish the task of instilling a sense of purpose to jury service, as well as usher gratitude for participants’ time and effort? The answer is most definitely a complicated one.

Carol believes that the courts need to better prepare jurors for the weight of the decision they are being asked to make. “In a trial that’s violent, not many people are prepared to process that sort of thing. Maybe you think you are because you saw it on the news or TV, but you aren’t – so make sure to tell the lawyers up front.”

Additionally, she notes that, by and large, jurors are eager to return a verdict quickly, so they can return to their normal lives. To those heading into the deliberation room, Carol asks that they spend as much time as they need to review every aspect of the case, “because it could be someone’s life on the line … and it matters.”

-“No remedy for anyone unless reform occurs…”

Now retired, Carol spends her time advocating for widespread reform of the felony murder rule, which she believes is an unfair application of the law, as it convicts individuals of crimes they didn’t actually commit. Motivated and inspired by the 1,100 families of Pennsylvania inmates serving life sentences based on such convictions, “Tinkering with the legislation is the only way to begin,” she concluded.

# # #

Frederick Burton, now named Muhammed, remains incarcerated in a Pennsylvania state prison.

# # #

The Worst Thing We’ve Ever Done: One Juror’s Reckoning with Racial Injustice (She Writes Press, April 2023, ISBN: 978-1-64742-460-2, $17.95)

Carol Menaker, author

![]()

You can pre-order your copy by using the links appearing below, or via any online bookseller.

# # #

DISCLAIMER: THE VIEWS EXPRESSED HEREIN ARE PROVIDED FOR INFORMATIONAL OR EDUCATIONAL PURPOSES ONLY AND ARE EXCLUSIVE TO THOSE INDIVIDUALS EXPRESSLY IDENTIFIED OR FEATURED IN THIS POST (AND ARE NOT SHARED BY THE PUBLISHER OF THIS WEBSITE).

THIS POST DOES NOT CONSTITUTE AN ENDORSEMENT OF ANY PERSON, PRODUCT, OR SERVICE DESCRIBED HEREIN.

NO CONSIDERATION OR REMUNERATION, OF ANY KIND, WAS EXCHANGED FOR THE PUBLICATION OF THIS PIECE.