GUEST COMMENTARY

GUEST COMMENTARY

The Planned Shrinkage

of Latino Political Power

in New York City

by José R. Sánchez (May 18, 2012)

The paradox of an apparent inverse relationship between Latino population size and Latino political power in New York City, while widely noted, has not been adequately explained. By looking at this community's history one can perhaps glean some evidence that can help shed light on the basis of this Latino political power paradox.

The paradox of an apparent inverse relationship between Latino population size and Latino political power in New York City, while widely noted, has not been adequately explained. By looking at this community's history one can perhaps glean some evidence that can help shed light on the basis of this Latino political power paradox.

The "Planned Shrinkage" Regime

In the 1970s, many New York City officials advocated a policy of " planned shrinkage " for some city neighborhoods. Earlier this month, The New York Times published a story about existing and rising influential New Yorkers that included no Latinos. There is, I would argue, a connection between the planned shrinkage of many Latino neighborhoods more than 40 years ago and the dearth of recognizably powerful Latinos in the city today.

Back in the '70s, NYC Housing Commissioner Roger Starr and others advocated withdrawing city services like fire and police from communities that were too poor and unnecessary for the city's survival. The idea was to protect cities during a fiscal crisis by withdrawing scarce resources from decaying neighborhoods and "undesirable populations." This policy of planned shrinkage caused the South Bronx and other poor communities to burn to the ground as a result, many have said. The consequences for the Puerto Ricancommunity were devastating. Made homeless, jobless, and scattered from their homes, these communities began to quickly loose the fervent and militant core of community organizations and leadership that had existed there. They also lost something less tangible - community knowledge and memory .

Many Puerto Ricans , pushed out of the Bronx , moved away to New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Florida where they often tried to reassemble their lives and recover an economic, social, and political stability. They were not always successful. Was it perhaps because they took with them the knowledge of how to organize tenants, how to mobilize a neighborhood, and how to draw upon the resources made available by work and community that did not fit well with their new community? They left behind in the Bronx the opportunity to build on the political and power achievements of the 1960s and early 1970s. As a result, Puerto Ricans and, by extension, all Latinos, lost an opportunity to build on the foundation of power that had been created since the 1950s.

The "Planned Shrinkage" Legacy

The consequence is that today Latinos are an important demographic and economic force in the city, but largely devoid of political power . There are many more Latino elected officials today than there were in the 1970s. Aside from the two Puerto Rican Congressionmembers from New York, there are many more local Latino elected officials. In the New York State Legislature, there are 6 Latino Senators and 14 Latino Assembly members. In New York City, Latinos hold 11 positions in the New York City Council (21.6%) and are 28.9% of the total population.

The Latino community has been shrunken, pushed, dismissed, and scattered. People who are on their way out usually don't get much attention. This is as true of fired employees as of term-limited politicians and community groups. Not only has the Latino population gone through a constant churning since the 1970s with new waves of Latino nationalities replacing earlier displaced Latino settlers, but policy makers now also expect and probably look forward to an overall shrinkage in the city's Latino population.

Planners recently predicted fewer Latinos would live in New York City in the near future. In 2006, demographers announced that "after 2010 more Hispanic people will be leaving New York than arriving." Despite this constant population churning and possible shrinkage, Latinos can point to many political achievements during the last 20 years. For example, a Puerto Rican, Fernando Ferrer, ran for mayor in 2001 and, for a brief period, Puerto Ricans chaired the Bronx Democratic County Committee.

These and other political achievements come with a caveat, however. Not only have these positions not delivered power, but they have also been coupled with many corrupt Latino politicians , especially in the pivotal area of the Bronx.

'splaining the Political Tragedy

of the "Four Amigos"

There are many reasons for the lack of power and the prevalent corruption. We can point to the diversity of the Latino population in New York , to its relative youthfulness, and to its general poverty. But I believe that the planned shrinkage, housing and residential devastation of the 1970s left a deep, unhealed gash on the ability of the Puerto Rican and Latino community to both build and capitalize on earlier political organizing achievements as well as to hold their elected officials accountable.

The best example of this complex and contradictory process is the strange story of a "gang" of mostly Puerto Rican elected officials, sometimes called the Four Amigos . This small group made a dramatic. Desperate and ultimately failed attempt in 2009 to wrestle power for themselves, if not for Latino New Yorkers. Their efforts illustrate, more than anything, the increasing divide between Latino elected officials and an unorganized and fragmented Latino electorate.

These three Puerto Rican officials, Pedro Espada Jr. , Hiram Monserrate , Ruben Diaz Sr., and non-Latino Carl Kruger had grand plans. Their stated reason for rebelling was that Latino lawmakers needed a greater voice in government. "We have a black president, a black governor, and we have a concern that we have to be sharing power," Mr. Díaz said at the time.

Now, three years later, Monserrate and Kruger are headed for jail, while Espada was just convicted for corruption . Only Diaz, a Pentecostal minister, remains in office. But the crafty coup they executed in an attempt to wrestle power from the State Senate blew up in their faces way before they found themselves in legal trouble. What went wrong, however, was not simply blowback from taking on the political establishment.

The main problem was that they had very little organized community support. And they lacked the support of unions or the party faithful while representing the poorest borough in the city. There was nothing substantial standing behind their quixotic efforts or to protect them from the expected backlash. In fact, they were opposed by some community organizations and constituents because they took positions that went against their community and city's interests. This was particularly the case with their rejection of the so-called Ravitch plan to increase bridge tolls to pay for mass transit increases. They were essentially alone .

In fact, the Four Amigos had actually made a strategic decision to seek friends in the suburbs and among Republicans. They must have decided that they could not find friends among fellow Democratic Party apparati or community organizations. Nor could they find friends with any power within their communities. So, they took a radical step into the foreign landscape of Republican and suburban political alliances . They hoped such extraordinary alliances would deliver them the power they otherwise could not gather from their own communities or political party.

Each of the Amigos came into politics from outside the Democratic Party system and they had contentious relations to the party during their terms in office. Diaz was a pastor when he entered the City Council in 2001 . Espada was the head of the Soundview Community Health Center when he was elected to the New York State Senate in 1993. The Health Center served about 45,000 patients a year, and included a computer literacy program and a senior lunch program. Monserrate was a policeman before he got elected to the City Council in 2002. And Carl Kruger was the only one with some party connections among the group of Amigos. He was Assistant Director of Member Services for the New York State Assembly for a decade, as well as the Chairman of Brooklyn Community Board 18 before he became State Senator in 1994.

What makes the group stand out is not so much what they did before they came into office but rather their tenuous connection to the dominant Democratic Party in the City during their rise to and stay in office. Each was essentially marginal to the Democratic political apparatus. And though each was able to garner enough public support to get elected, the support did not come with any stable or organized community, labor, and party organization. Ultimately, this made them not only weak but also unaccountable to the public interest.

A Community Caught in Political Shrink Wrap

Why did Latino elected officials embark on such a risky and ambitious venture? Again, the answer can be traced in large part to the planned shrinkage of Latino communities, especially in the Bronx. This shrinkage depopulated neighborhoods, reduced population density, reduced the amount and quality of interactions between residents, and introduced the conservative influence of single and two-family home ownership to replace the burned down tenements. The result was a Latino resident population with few longstanding ties to the community, little community memory, constantly shifting Latino national origins, and increasingly conservative values drawn from homeownership.

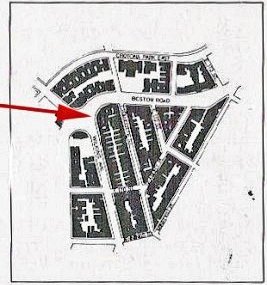

The demographic changes caused by the planned shrinkage of so many Bronx communities are clear and striking when mapped. This one section of the Bronx near Crotona Park (see map below) was a typical densely populated block of tenements until the mid 1960s. In fact, " three thousand people lived in 51 apartment buildings on the two blocks at the center of the neighborhood. Today, only one of those buildings remains standing, Number 1500, built in 1915, at the corner of Boston Road and what was then Wilkins Avenue ." (see red arrow)

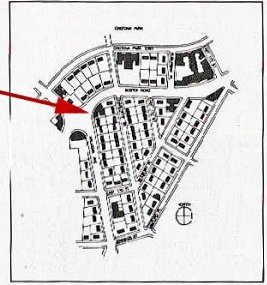

By the 1980s, this same section was completely devastated of houses and population, as the map below shows. The empty, rubble-strewn blocks that were left behind by the epidemic of fires attracted a lot of national and public attention. Eventually, local and national political interests committed public resources to building private detached homes on those lots. This deeply flawed urban policy brought suburbia to the Bronx, ignoring decades of urban planning principles as well as the desperate housing needs of city residents.

The result was a shrunken residential population, an unstable tenement population of tenants competing for scarce rental apartments, and an increasingly conservative Latino and African American population of homeowners. The construction of single-family homes, like those at Charlotte Gardens, in the 1980s remade the political as well as the residential landscape for Latinos in this and other parts of the Bronx.

This aerial view (below left) of this area in the Bronx demonstrates the absurdity and dysfunction of this urban plan. As described by one source, the remaining " New Hope Plaza at the corner has homes for some 100 people in 38 households (and three stores too), while the entire rest of the block has just 18 housing units, fewer than half the number in New Hope Plaza ."

There is no question that the shifting tides of incoming Dominican, Honduran, Puerto Rican, and Mexican residents in this part of the Bronx bring hope and energy. But the differences in citizenship status, immigration history, political focus, employment and economic status, as well as knowledge of the city, between these different Latino groups are often too difficult to bridge.

The results are often a lack of real community cohesiveness and leadership that cannot overcome the structural damage done by planned shrinkage. Thus, while Latinos have numbers on their side, they have very little else that can help deliver power. We should no longer be surprised that the New York Times can published a list of powerful New Yorkers in May 2012 and not include a single Latino on that list.

José Ramon Sánchez is Associate Professor of Politics and Chair of Urban Studies at Long Island University - Brooklyn; and Co-founder and Chair of the Board of the National Institute for Latino Policy, Inc. He is also the author of Boricua Power: A Political History of Puerto Ricans in the U.S. (2007) and co-author of The Iraq Papers (2010). Dr. Sánchez is currently working on a chapter on Latino politics for the forthcoming 2nd edition of Latin@s in New York: Communities in Transition. He can be reached at jose.sanchez@liu.edu .