A NiLP iReport

The Racial-Ethnic Diversity of Latino Elected Officials in NYC

By Angelo Falcón

The NiLP Report

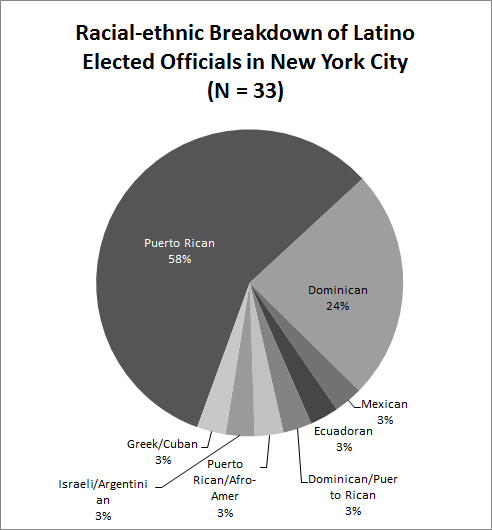

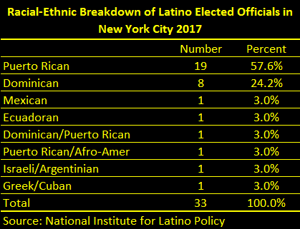

The recent endorsement of NYC Mayor de Blasio by three Dominican elected officials in Washington Heights raised some interesting questions about the nature and future of Latino politics in New York City as the mayoral election occurs this year. As the article about this endorsement referred to the endorsers as Latino political leaders, the fact that they were all Dominican (with a Puerto Rican elected official looking on) poses the issue of the degree of pan-ethnicity and its role in the city's Latino politics.

What is the racial-ethnic make-up of New York City's Latino elected officials and what impact, if any, does this have? The media has the tendency of discussing Latino politics in global terms like "Latino" or "Hispanic." However, New York has possibly the most diverse Latino population of any city in the country, with members from over 21 predominantly Spanish-speaking countries. Is this diversity reflected among this community's political leadership and does it matter if it does or not? Unfortunately, despite the fact that close to one-in-every-three New Yorkers are Latino and are one of the fastest-growing groups in the city, very little has been written on the subject or acknowledged by the media..

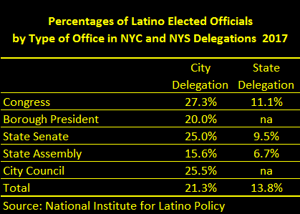

Our review of the city's elected officials finds that there are currently

33 Latinos holding office in the U.S. Congress, State Senate, State Assembly,

City Council and as Borough President. Overall, Latinos make up 21 percent

of those in these offices representing New York City only (not the rest

of the state). By office, Latinos make up 27 percent of those in the city's

Congressional delegation, 25 percent of those in the city's State

Senate delegation, 16 percent of those in the city's State Assembly

delegation, 26 percent in the City Council, and 20 percent of the Borough

Presidents. This means that regarding population share (29 percent), Latinos

are generally underrepresented in elective office. It is perhaps ironic

that Latinos, however, almost achieve parity in Congressional and State

Senate seats in which their representatives are almost entirely in the

minority party in those bodies, while being most underrepresented in those

bodies in which the Democratic Party, with which Latino elected officials

are almost entirely affiliated, is in the majority.

Our review of the city's elected officials finds that there are currently

33 Latinos holding office in the U.S. Congress, State Senate, State Assembly,

City Council and as Borough President. Overall, Latinos make up 21 percent

of those in these offices representing New York City only (not the rest

of the state). By office, Latinos make up 27 percent of those in the city's

Congressional delegation, 25 percent of those in the city's State

Senate delegation, 16 percent of those in the city's State Assembly

delegation, 26 percent in the City Council, and 20 percent of the Borough

Presidents. This means that regarding population share (29 percent), Latinos

are generally underrepresented in elective office. It is perhaps ironic

that Latinos, however, almost achieve parity in Congressional and State

Senate seats in which their representatives are almost entirely in the

minority party in those bodies, while being most underrepresented in those

bodies in which the Democratic Party, with which Latino elected officials

are almost entirely affiliated, is in the majority.

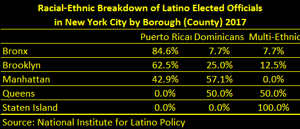

Borough. Geographically, the Latino elected officials were broken down by borough as follows: 36 percent in the Bronx, and 63 percent of those in Brooklyn. Dominicans are 57 percent of those in Manhattan and 50 percent of those in Queens. Staten Island has one Latino representative who is of Greek/Cuban heritage. The Bronx continues to be the major Latino political stronghold in the city, followed next perhaps by Manhattan and Brooklyn equally. Among Latino elected officials, Queens' Latino population is the most underrepresented given its size, which has been the case historically. Staten Island is an outlier in this regard with a Greek/Cuban Assemblymember who is the only Latino Republican in the city.

Type of Office. By elected office, Puerto Ricans make up 67 percent of the city's Latino Congresspersons, 67 percent of the State Senators, 60 percent of the State Assemblymembers, 54 percent of the City Councilmembers and the only one Latino Borough President (The Bronx). Dominicans make up 33 percent of the Latino Congress members, 38 percent of the City Councilmembers, 33 percent of the State Senators, and 10 percent of the State Assemblymembers. The remaining multi-ethnic Latinos make up 30 percent of the Assemblymembers and 8 percent of the Councilmembers, with none in the Congress and State Senate.

Latinos make up of the following percentages of the city's delegations for these political offices: 27 percent of the Congressmembers; 25 percent of the State Senators; 16 percent of the State Assemblypersons; 26 percent of the Councilmembers; and 20 percent of the Borough Presidents. These levels of representation are surprising in the light that the expectation is that Latinos would be best represented at the smaller districts of the Assembly than at the other much larger districts, but Latinos are only 16 percent of the city's Assembly delegation compared. For example, to the 27 percent of its Congressional.

We may also see the addition of another layer of Latino elected officials next year if the current appointed acting Brooklyn District Attorney, who is Puerto Rican, is elected to the post in November. This would be the first time a Latino would be elected to one of the five district attorney posts in the city. While there was an effort to elect a Latino to this position in the Bronx last year, despite the Puerto Rican political dominance in the borough, this didn't occur.

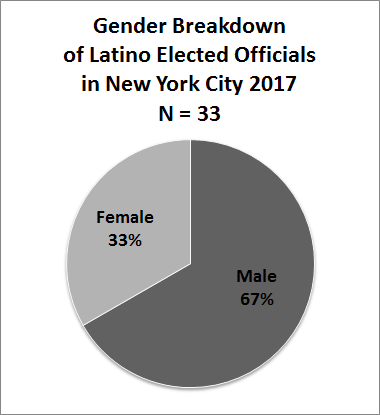

Gender. Of the 33 Latino elected officials in New York City, 11 or 33 percent

of the total are women. By elective office, women comprise these shares:

33 percent of the Latino Congress members, 17 percent of the State Senators,

30 percent of the State Assemblymembers, 46 percent of the City Councilmembers,

and the only Latino Borough President is a male. The Council Speaker is

a Puerto Rican woman, and the first Latina ever to serve in this leadership

position. By racial-ethnic identity, 50 percent of the Latin female elected

officials are Puerto Rican, 30 percent are Dominican, and 20 percent are

multi-ethnic. All the Latina elected officials in the Bronx and Brooklyn

are Puerto Rican, 60 percent of those in Manhattan are Dominican, and

in Queens, there is one Dominican and one multi-ethnic Latina elected

official, and no Puerto Ricans. The one Latino elected official in Staten

Island is a woman of Greek/Cuban descent. The New York City Council has

historically had the best representation of Latina women than the other

levels of government in New York, with at one point Latina women making up a

majority of the Latino Councilmembers. Except for Borough President, Latinas are

represented at all three levels of government in New York City.

Gender. Of the 33 Latino elected officials in New York City, 11 or 33 percent

of the total are women. By elective office, women comprise these shares:

33 percent of the Latino Congress members, 17 percent of the State Senators,

30 percent of the State Assemblymembers, 46 percent of the City Councilmembers,

and the only Latino Borough President is a male. The Council Speaker is

a Puerto Rican woman, and the first Latina ever to serve in this leadership

position. By racial-ethnic identity, 50 percent of the Latin female elected

officials are Puerto Rican, 30 percent are Dominican, and 20 percent are

multi-ethnic. All the Latina elected officials in the Bronx and Brooklyn

are Puerto Rican, 60 percent of those in Manhattan are Dominican, and

in Queens, there is one Dominican and one multi-ethnic Latina elected

official, and no Puerto Ricans. The one Latino elected official in Staten

Island is a woman of Greek/Cuban descent. The New York City Council has

historically had the best representation of Latina women than the other

levels of government in New York, with at one point Latina women making up a

majority of the Latino Councilmembers. Except for Borough President, Latinas are

represented at all three levels of government in New York City.

How should we be discussing the politics of the 2.4 million Latinos in New York City, who make up 29 percent of the city's population? Given the racial-ethnic and geographic diversity of this community, is it more useful to look at it in broad terms like "Latino" or "Hispanic," or focus on specific national origin groups and their interactions? The answer appears to be that both of these levels of abstraction need to be utilized because each reflects different realities that need to be understood.

Despite their population decline and no longer being the majority of Latino in New York City, Puerto Ricans remain the majority of Latino elected officials in the city. This is the result of at least to factors: 1. Puerto Ricans being the only Latino group that comes to the city already as U.S. citizens from Puerto Rico; and 2. Their longer history of migration to New York going back to the 1860s. This has put Puerto Ricans in the challenging position of being major political gatekeepers in the Latino community.

Dominicans are the second largest group of Latino elected officials, with their ranks being among the fastest-growing. Dominicans, once concentrated in Washington Heights are now present in significant numbers in The Bronx, Brooklyn, and Queens. Population trends indicate that Dominicans are in line in the next few years to outnumber Puerto Ricans, making the political implications of this an interesting issue to track.

The other Latino groups have had some difficultly in breaking into electoral political representation. The fastest-growing and third largest group, Mexicans, only recently elected one of their own to the City Council, while the 4th largest group, Ecuadoreans, elected one of their own relatively recently to the State Assembly. Although their presence in the Latino population is minimal, Cubans and Argentineans have elected one of each, both to the State Assembly. A growing problem when discussing Latino politics at the national-origin level has been that the focus is usually on Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, rendering Mexicans, Ecuadorians, Colombians and other Latinos almost invisible except as "immigrants.".

The political issues raised by this diversity and its distribution among the Latino elected officials includes whether they function on unified pan-ethnic terms or separately along national-origin lines. The general tendency by the media is to refer to this community largely in pan-ethnic terms while ignoring its internal political dynamics. While the argument can be made that discussing this population's politics as "Latino" is basically a reflection of its internal dynamics, doing so uncritically ignores significant internal differences of the specific national-origin groups. Latino politics is both the sum of Puerto Rican, Dominican, Mexican, Ecuadoran, etc. politics, as wellas deined by its collective character.

Geographically, the Bronx is currently the political center of Latino politics in New York City, and largely a Puerto Rican stronghold. A second important political center is Northern Manhattan, which is largely Dominican. In the rest of the city, Latino political representation is more diffuse. With the dramatic growth of the Dominican population in the Bronx (which now outnumber those in Manhattan), it is expected that this could result in greater Puerto Rican-Dominican political competition in the borough.

In Queens, there is the possibility of an Ecuadorean State Assemblyman challenging a Dominican City Councilwomen, while in Brooklyn, a sitting Mexican Councilmember may see challenges by a number of Puerto Ricans and a Cuban for his seat. While in the media, these are largely discussed as Latino-versus-Latino contests, the underlying national-origin dynamic involved is usually downplayed or ignored, limiting a fuller and possibly more useful understanding of the "Latino politics" involved.

Looking at how the Latino elected officials themselves frame Latino politics reveals a highly fragmented projection of it. While in the 1960s-90s there was more of a focus on Latino empowerment on a citywide level, currently Latino politics is projected on a largely localized or even individualized level. It is important to note that historically, Puerto Rican residential settlement in New York City was, for example, much more dispersed than that of African-Americans, resulting in Puerto Ricans having much more of a tendency to establish citywide organizations and strategies, while African-Americans focused on on a more local neighborhood-based approach. This led to the creation of citywide Puerto Rican social agencies that have largely atrophied over the years. On the other hand, from their more recent migration of the mid-1960s, Dominican settlement in the city concentrated initially in the Washington Heights section of Manhattan, and this concentration largely followed the African-American model, but over the years followed the more dispersed Puerto Rican pattern outside of Northern Manhattan into the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens.

Compared to these groups, the city's Mexican population is one of the most dispersed, although a significant concentration now exists in the Sunset Park neighborhood of Brooklyn. Queens, on the other hand, is where other Central and South Americans are concentrated, as well as Puerto Ricans and Dominicans, a borough in which Latinos have the longest history of political underrepresentation. In Staten Island, the Latino population is largely on its North Shore and includes many higher income Puerto Ricans and low-income Mexicans and other Latino immigrants. The one Latino elected official in Staten Island, however, is a conservative Republican whose politics is not in the mainstream of Latino politics locally or nationally.

Returning to the Dominican elected officials' endorsement of Mayor de Blasio with which we began this report, it is interesting that this support for his candidacy came in this national-origin form. One explanation for this was Mayor de Blasio's approach to Latinos stemming from the support that his African-American opponent, Bill Thompson, received from the larger Puerto Rican political leadership in the Bronx, prompting him to emphasize his Latino outreach to non-Puerto Rican Latinos. The possibility, although slight, of the Bronx Borough President, Ruben Diaz Jr., of running for Mayor with the backing of New York Governor Andrew Cuomo reinforces this interpretation of the relationship. This was the reason, for example, that Mayor de Blasio refused to ever meet during his entire first erm with the Campaign for Fair Latino Representation to address the problem of his poor record of appointing Latinos to his administration, in apparently having perceived it as a primarily Puerto Rican advocacy effort that he had to neutralize politically. This is a good example of the importance of understanding the interior composition and nature of Latino politics.

The election of the first Dominican to the United States Congress last year is another example in which looking at the Latino national-origin factor was important. While much of the discussion in the media coverage of that series of races over two campaigns was on the role of the Latino vote in general, the results showing that while Adriano Espaillat consistently had the Dominican vote in Washington Heights, Inwood and the West Bronx, he consistenly lost the Puerto Rican vote in East Harlem.

In the upcoming election this year for the City Council, the bid for reelection by Julissa Ferrera-Copeland, who is Dominican, in Queens will also likely involve Latino national-origin competition. That is, if State Assemblyman Francisco Moya, who is Ecuadorean, and former State Senator/Councilmember Hiram Monserratte, who is Puerto Rican, decide to run against her, as they have indicated.

By looking more closely at the internal composition of Latino elected officials, one gains a deeper insight into the nature of Latino politics in New York City today. The tension between the pan-ethnic and national-origin features of this community is what together helps define its politics, at least in New York City as it interacts with the city's political mainstream. It would also be interesting to explore this question in other cities across the country to see if it is the case more generally.

Angelo Falcón is President of the National Institute for Latino Policy, for which he edits The NiLP Report on Latino Policy & Politics. He is also one of the co-editors of the forthcoming book, Latinos in New York: Communities in Transition, 2nd Edition, being published by the University of Notre Dame Press in June 2017. He can be reached at afalcon@latinopolicy.org.

_______________________________________________________________________________________________________

The NiLP Report on Latino Policy & Politics is an online information service provided by the National Institute for Latino Policy. For further information, visit www.latinopolicy. org. Send comments to editor@latinopolicy.org.